This article outlines 18 best practices for working with data in Google Sheets.

It’s a compilation of my own experiences of working with data in spreadsheets for 15+ years, along with the opinions of others I’ve worked with and reports and articles I’ve read online.

By no means is it meant to be exhaustive or the last word on the subject, but if you follow these guidelines, you should have a robust data workflow.

Following these best practices for working with data will make you more efficient and reduce the chance of errors creeping in. It’ll make your work easier to follow and understand and add value to your team’s or client’s workflow process. It’s a good habit to have, and it’ll serve you well as you progress with your data career.

Contents

- Organize your data

- Keep a backup copy of your data

- Document the steps you take

- Go with wide-format data tables

- Use good, consistent names

- Use data validation for data entry

- Even better, use Google Forms for data entry

- One cell = one piece of information

- Distinguish columns you add

- Don’t use formatting to convey data

- Add an index column for sorting & referencing

- Format the header row

- Freeze the header row

- Turn formulas into static values after use

- Keep copies of your formulas

- Create named ranges for your datasets

- Avoid merged cells

- Tell the story of one row

Learn more

Learn moreLearn how to make data-driven decisions using Google Sheets in the Data Analysis with Google Sheets course

18 best practices for working with data

1. Organize your data

Projects are more likely to be successful when there is good communication and a good organizational structure. A big piece of that is good data management, and that starts with implementing a well-organized, logical and efficient folder structure.

As your projects grow in size, it becomes more and more crucial to keep your Google Sheets organized in a meaningful way.

At a minimum, you’ll have a top level project folder and inside that, you’ll want separate folders for your raw datasets, for your analysis and for your final deliverables. Files can move from one folder to the next (or be copied from one folder to the next) as the project progresses.

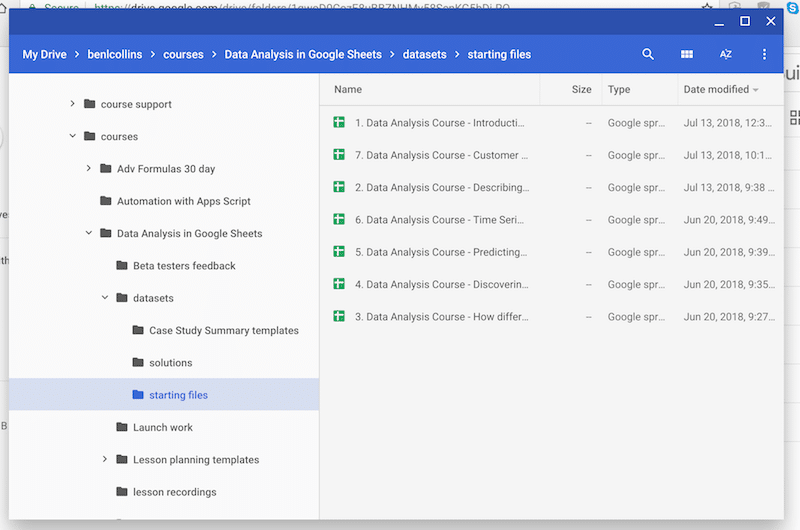

Here’s an example from my Drive, with folders for each course I’m working on, and sub-folders within them:

2. Keep a backup copy of your data

Surely this is redundant in the age of cloud data, right?

On the one hand yes, there shouldn’t be a need to backup your Google Sheets.

Google has so much redundancy built in, your data should be safe from getting corrupted or lost. And you can rely on version history to go back in time to an earlier version of your Sheet should you need to. You can restore files from trash, although once you’ve deleted them from trash they really are gone for good (I believe there’s an exception for admins of school G Suite accounts however).

So your data should be safe.

On the other hand, however, your account could still get hacked or a colleague could (accidentally) delete a crucial file, and you could lose data that way.

For anything that’s really important, it’s worth making a copy, either in a different google account if you have one, and/or offline (as a CSV or excel file).

It’s definitely not necessary for everything, just your mission-critical stuff.

It’s also worth mentioning that making a copy of a Sheet means the new copy does not have the version history, which can be an advantage or disadvantage depending on your situation. It’s generally a good idea if you’re sharing the Sheet and don’t want anyone to be able to see all your workings to get to the final result (maybe you deleted confidential data for example).

3. Document the steps you take

This is often left as an afterthought or worse, just not done at all. However, it’s absolutely one of the best practices for working with data. It just requires a little effort.

There’ll come a day when you’re glad of some notes about where your data came from, what assumptions you made, what calculations you decided to do, and how you did them!

It doesn’t need to be super long, just enough detail to allow you or someone else enough information to understand and recreate the analysis.

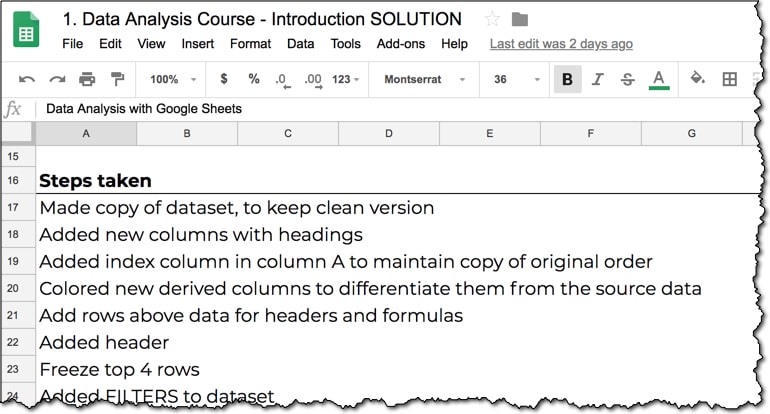

This is example is deliberately detailed, so I wouldn’t suggest you need to create something like this everytime:

However, it would be worth mentioning where your data came from, what major steps or tests you did, and how you did them (e.g. “Ran pivot table to determine aggregate sales metrics”), as well as any assumptions you made.

If you’re creating a dataset, then you should also create a data dictionary, where you explain what data each column holds. A data dictionary is just a list of column headings in a separate tab, with a note explaining each column, for example, what the units are, whether it’s been normalized, how it’s been calculated etc.

4. Understand wide-format and tall-format data tables

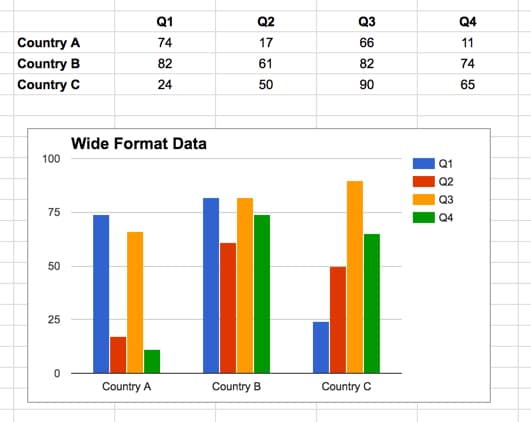

As spreadsheet users, we typically use 2-dimensional, wide-format tables.

The rows and columns represent categories or measures (for example, regions vs. months). It’s easy to understand this grid format and charts and calculations lend themselves better to this layout since you can run calculations across rows or columns.

The Google Sheets chart tool expects data in a “wide-format” table rather than a traditional “tall-format” table (which is how data is stored in databases).

This “wide-table” format makes it easy for the chart tool to parse the data and show it correctly.

There are no blank rows or columns. The X values (the Countries) are in the first column and the series names (the Quarters) are in the first row.

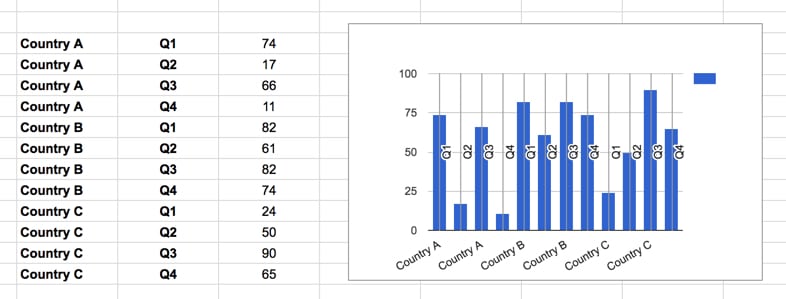

Contrast that with a “tall-table” format (how a database typically stores data) and you can see the chart tool cannot correctly parse and show the data.

However, the tall-format datasets work much better for doing data analysis, with Pivot Tables or the QUERY function.

To transform tall data into wide data is called a pivot.

To transform wide data into tall data is a harder operation and is called unpivot. Here’s how to use the FLATTEN function and the SPLIT function to unpivot in Google Sheets.

Note: this is not a case of right and wrong, and you’ll encounter data in both formats and even in between. It’s about using the right shape for the context of your situation.

Do you want to create a chart from your data table? Go wide! Do you want to export your data table as a CSV for uploading to your company database? Maybe you’ll need to create a tall format table then.

For further reading on this subject, check out this excellent post, Spreadsheet Thinking vs Database Thinking, from Robert Kosara.

5. Use good, consistent names

As your projects grow in size and complexity it pays to develop a consistent naming strategy for your Sheets, for tabs, named ranges, variables, and column headings.

Historically, computer programmers have avoided spaces in variable names, and although it’s not strictly necessary in Sheets, it’s still a good idea to avoid spaces and non-alphanumeric characters in tab names, named ranges and column names.

Why?

Certain functions (e.g. inside the select statement of the QUERY function) and certain add-ons still adhere to this strict no-space rule, so although not very common, it will save you hassle.

The preferred approach is to use camel case or underscore notation, and you can choose whichever you prefer, e.g.:

customerData

customer_data

6. Use data validation for data entry

One of the most time-consuming tasks data practitioners face is tidying up and cleaning data.

The problem is more acute wherever there is user-generated content. Invariably, everyone will use different notations (e.g. US, USA, United States, America, US of A,…), or misspell names, or enter dates with month first vs. day first, etc.

Anything you can do to preempt this will save you lots of time on the back-end when you’re working with the data.

One method is to use Data Validation to control what a user can enter into a cell. For example, you could present them with a drop-down list of choices (instead of a free-form field), or restrict the cell to numbers only, or to positive numbers only, or all sorts of other data validation options.

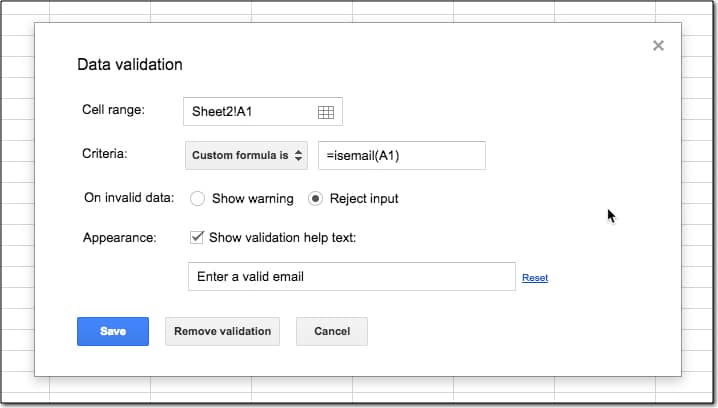

Here’s a more detailed example, combining the ISEMAIL function with data validation to ensure only valid email addresses can be entered into your Sheets, ensuring better data accuracy going forward.

In the cell where an email address will be entered, for example A1 in the image above, right click and choose Data Validation... or go to Data > Data Validation... menu option, which opens this popup.

Choose Custom Formula in the second option and enter =ISEMAIL(A1), as shown in this image:

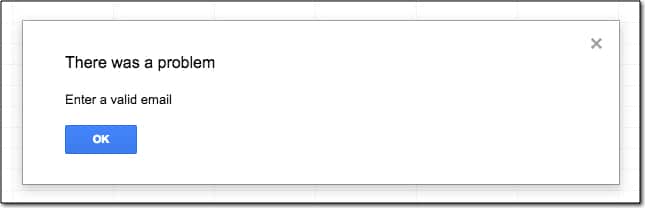

This prevents a user from entering an invalid email, or anything other than an email, into that cell, and displays a warning sign and leaves the cell empty:

Learn more

Learn moreLearn how to make data-driven decisions using Google Sheets in the Data Analysis with Google Sheets course

7. Even better, use Google Forms for data entry

Google Forms are an even more robust way to collect user inputs because it separates the data collection from the data storage/analysis. This will prevent users from accidentally (or intentionally) overwriting data and/or seeing data from other users.

They’re super easy to set up and pair seamlessly with Google Sheets. I use them for all of my own audience surveys and course feedback surveys.

I’ve written about using Google Forms before, in this article.

8. One cell = one piece of information

Each cell should contain just one piece of information. Don’t be tempted to put more than one datapoint into a cell.

Cells with single data points can be used in formulas and charts without issues. Those with multiple data points, well, they can’t.

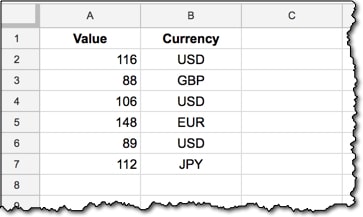

For example, if your dataset has different currency values, then you’ll want to use two columns to record the data, one for the value, and one for the currency, like this:

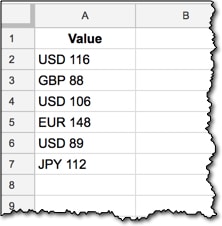

This is much better than having a column like this in your dataset:

Note, you often get data in this format, with multiple data points encoded in a single cell, and it’s your job to split that data out into separate columns, so you can do your analysis.

9. Distinguish columns you add (e.g. by color)

It’s helpful to be able to distinguish the original raw data from any columns you’ve added in the course of your analysis. You’ll quickly lose track of the original data columns if you don’t mark them, and I’ve found adding a subtle color to the whole column is the quickest and most reliable way of indicating this.

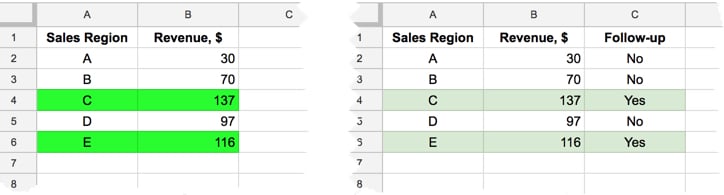

Can you tell which are the original and which are the columns I’ve added in this example?

10. Don’t use formatting to convey data

Another color tip amongst the best practices for working with data in Google Sheets!

Don’t use formatting exclusively to communicate data, merely to augment underlying data.

Having just told you in the previous tip to distinguish columns by color, I’m now telling you not to? What?!?

This is different.

In the previous point, color was used to make your life simpler, to help you quickly identify what was original data and what was calculated columns you’ve added. It’s not communicating data, it’s simply facilitating a more efficient workflow.

In this case, suppose you want to classify revenue numbers into ones that require follow up versus ones that don’t. If you use cell highlighting to identify the ones you want to follow up with, you risk that not being understood by other users or worse, being lost if you export your Sheet to CSV, or someone decides to make wholesale changes to the formatting.

You want to avoid the situation on the left, and instead follow the example on the right, where data is communicated explicitly:

The color is merely a tool to aid comprehension, to make it easier and quicker for the user to work with your data.

11. Add an index column for sorting & referencing

Anytime you find yourself sorting your data, for example to rank largest to smallest for metric X, then you’ll want to add an index column, which will allow you to always get back to the original order.

It’s a simple numeric counter on each row, starting from 1 and going up to the last row of your dataset:

You’ll notice that it’s a colored column, meaning it’s one that I’ve added to the dataset.

I’ve been stuck before, unable to reverse the numerous sorts I’d performed and left with a dataset in an order than no longer made sense. There’s a number of reasons why you might want to get back to the order the data came in, perhaps to check for the sequence transactions happened in, perhaps to explain your steps to somebody else, or for sharing the data with other users.

12. Format the header row best practices for working with data

Center your column headings.

Wrap header text.

Make header text bold.

That’s all!

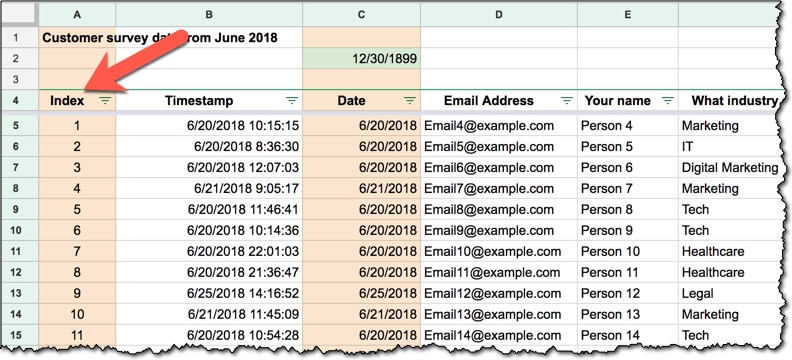

13. Freeze the header row

Hopefully this is already one of the best practices for working with data that you follow.

This should be something you do automatically without thinking. It’s essential once you have more than 20 rows of data, otherwise you’ll lose track of your column headings.

Find this in the View menu: View > Freeze > Up to current row

This is how locked top rows behave when you scroll:

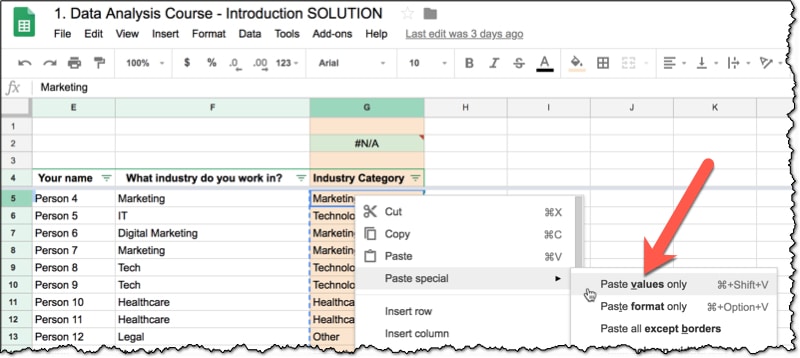

14. Turn formulas into static values after use

Once you’ve used a formula, it’s generally a good idea to turn those “live” formulas into static values, provided you don’t need to keep them active.

There are times when you need to keep your formula active because your data is changing and you want the formulas to update in real-time. In that case, it’s totally fine to leave “live” formulas in your dataset.

However, if you’ve used a formula to derive a column, for example an IF based on a static date column, and it’s not going to ever change again, then you should change the column into static values.

Highlight the whole column and copy the data (Cmd + C on a Mac, or Ctrl + C on a PC/Chromebook).

Then over the top of this same data range, Paste-Special-As-Values.

Either right click and select Paste special > Paste values only or use the shortcut: Cmd + Shift + V on a Mac, or Ctrl + Shift + V on a PC/Chromebook.

This will help to make your Sheets run quicker, which is an important factor if you have large amounts of data.

15. Keep copies of your formulas

In the previous step, I advocated turning formulas that you’ve used into static values, once you’re finished with them.

However, you should definitely keep a copy of them!

You’ll thank yourself later when you need to re-use it, and you have it available, or when someone asks you how you derived a certain column.

By far the most convenient way to keep a copy of formulas is to paste a live copy into a row above your dataset and leave it there. That way it’ll keep all the relative references intact, so you can quickly copy it into your dataset to use again.

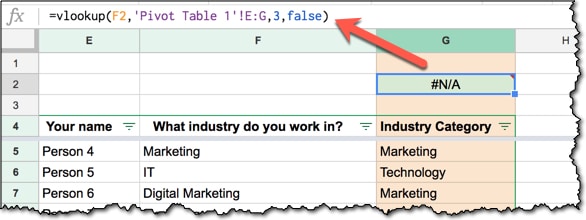

Here’s an example and you’ll notice that I’ve colored the formula green, to indicate I have a live formula in that cell:

Don’t worry if the formula shows an #N/A!, a blank cell or even a wrong answer, what matters is that it keeps the relative references intact.

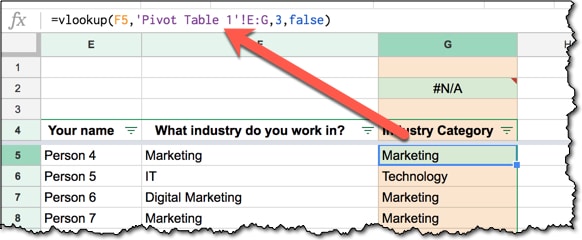

You can simply copy the formula from your column into the row above, and vice-versa, and know that it’ll just work:

Once you’ve copied your formula into the row above your dataset, feel free to copy-paste-special-values and turn the column into static values as per the previous best practice.

Important Note: Purists will argue that you should have a single header row and nothing more. I think there are pros and cons to this header-row-only approach and the “utility” row approach I’ve advocated here.

I use both methods, but tend to favor the approach of having a few “utility” rows because I think the benefits of keeping copies of formulas above your data analysis workings is worth the small price to pay to not start in row one. And once you’ve setup your named ranges, the issue falls away anyway.

One scenario that I would definitely go with a single header row approach is if I was creating a flat dataset (no formulas) to be shared.

16. Create named ranges for your datasets

This is a good habit to get into, and saves you having to manually highlight your data or type in the range reference every time you refer to your data in a formula.

It’ll reduce errors from incorrect range references or mixing up relative/absolute references, and has the added benefit of making your formulas clearer to understand.

Find it in the Data menu: Data > Named ranges...

It’s the difference between this, clean simple syntax:

=QUERY(countries,"SELECT B, C, D ORDER BY D ASC",1)and this, where you have to highlight the range you want:

=QUERY(Sheet1!A1:D234,"SELECT B, C, D ORDER BY D ASC",1)17. Avoid merged cells

One of the most important of the best practices for working with data in Google Sheets.

Merged cells should be avoided in datasets.

They cause all sorts of problems in datasets: they break formulas, nobody will know which column or row they relate to, your data gets overwritten, etc…

I’m not suggesting you never use merged cells (here’s how to use merged cells in Google Sheets correctly), because they can be useful.

For example, they let you position elements when you’re building front-end applications for Google Sheets and you want to get a certain layout, as shown in the header of this Facebook dashboard:

Just not in your datasets, ok!

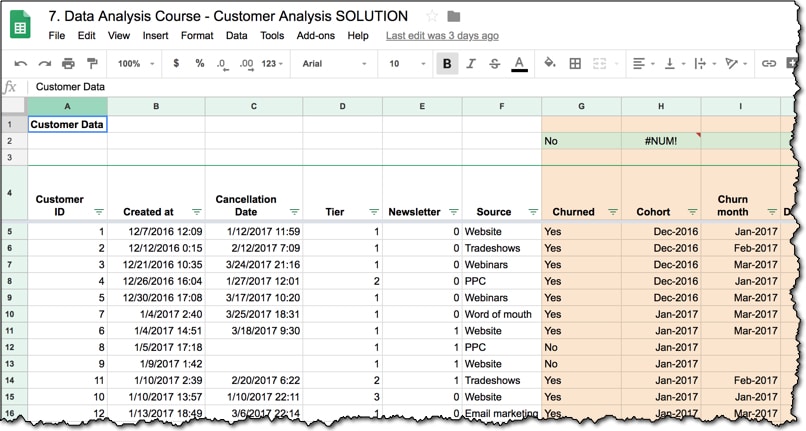

18. Tell the story of one row

This is perhaps my favorite of the 18 best practices for working with data, because it’s so simple but so effective.

This is a useful tip I picked up from a data scientist at General Assembly in Washington, DC, when I was teaching their Data Analysis course in 2015/16.

The idea is to read (out loud if you like!) across one row of your data and really see and understand what’s in every column.

It’ll help you know what data is in your dataset, or prompt you to investigate further if you don’t understand what a column shows. Potentially it’ll save you doing unnecessary work, because you’ll know exactly what you have.

Developers often keep yellow rubber duckies sitting on their desks to debug their lines of code, so go ahead and follow their example if you like!

Further reading:

A tweet from data scientist Hadley Wickham, containing a wealth of ideas and opinions.

Data organization in spreadsheets, a research paper by Karl Broman and Kara Woo.

Best Practices for Using Google Sheets in Your Data Project by Matthew Lincoln.

Anything you’d like to add? Do you follow any best practices for working with data that are different from what I’ve described here? Drop a note in the comments!

Much appreciated! Have you considered making this available as a pdf or google doc so that users can have a portable/printable copy ? Looking forward to your Analysis course!

Thanks Lon! Yes, I have plans to turn a few of the longer posts into ebooks at some stage (this one, the slow Sheets one, the beginner guide…). Don’t have a definite timeline yet, but I’ll post it here when I do. Maybe I should combine all of them into a single Google Sheets book, who knows?!? 😉

Hi Ben,

Thanks again for this as all your points are very valuable. The only advise I can add is to have “Data” Sheets that have the data headers in the Row 1, unlike your example in point 13 that starts on row 4.

The reason I suggest this is for the following:

1. When using ranges in your formula you know the range will always start in A1 and not A3 or A4. Example =Sheet1!A:M and not Sheet1!A3:M

2. You can also use the Format “Sheet1!1:1000” as you do not need to know how many Columns you have. (helps when using INDIRECT)

3. With all the above your name ranges are easier to maintain.

Hopefully this helps

Hey Shane!

Thanks for your comment. It’s a great point you mention. I think there are pros and cons to both approaches. I’ve used both approaches, but tend to use the approach of having a few “utility” rows above more often.

Purists will argue of course that you should only ever have a single header row and nothing more, and I would do that if I was creating a flat dataset (no formulas) to be shared. But I think there are benefits of keeping copies of formulas above your data analysis workings, and it’s worth the small price to pay to not start in row one. And once you setup your named ranges, the issue falls away anyway.

I will add a comment to this effect in the post. Thanks! 🙂

Cheers,

Ben

True Ben when it comes to seeing the formula’s in data sets to have them above. I normally use a Note on the data header with the formula as I always try to use Array formula’s with my data. I hide my formula in the header so as not to have issues when the data is sorted or filtered.

example : Instead of having a Formula in row 2, I would use something like ={“Total Sales”;ArrayFormula(C2:C*D2:D)}

I have a tendency to create notes (per cells) of descriptive rows/columns so that I or others understand the intent of the data set input/gathered/compiled.

John – that’s a great idea. Developers are better at including comments in their code to explain what they’ve done to others (and for themselves), but we spreadsheet users don’t seem to do it very often, or at all. So adding notes is a worthy investment of time because it’ll save you headaches in the long run.

Cheers,

Ben

Great post as usual. Thanx a lot.

One suggestion in point 15 of keeping the formula in rows above header.

The formula can be kept in the note of the column head cell. That way formula will remain intact and there will not be any need for any row above header row.

Yes, that’s another nice way to do it. Thanks for sharing SK!

Another tip I picked up from Jay Atwood has been to import data, if moving from Excel to Sheets, rather than simply copying and pasting. Not sure if that relates or is true.

Thanks for sharing Aaron!

“15. Keep copies of your formulas” Was an invaluable tip for me.

I am a novice on a fast track to learning Google sheets . I was thinking that this would be a sensible approach but it was very helpful to have the voice of experience confirm it.

My main use of excel is to analyse downloaded bank statements and would love to see this used as an example in your tutorials. There is so much information to be gleaned from them (eg. shopping locations to calculate trip expenses)

Hi Ben,

In the case of item 14, Turn formulas into static values after use, what about to use another sheet and import the values with importrange formula? so we automate the process of copy/paste from our process and still have the data as “static”/value (not a formula).

Hi,

Can we use a range in a online sheet from offline sheet. Like =vlookup(“from online sheet”, “From offline sheet”,0), Is this possible?

Thanks.

Thank you! I’m trying to use Sheets as a quick’n’cheap database for a charity, and your thoughts are very helpful.

You’re welcome! 🙂

I’m starting to get stuck into this now, and am currently looking at raw data in one workbook (not accessible to most people) and reports in another workbook, using QUERY, FILTER and IMPORTRANGE. I am writing scripts to offer a range of reports from the menu and place the results into a sheet, probably with any charts in another sheet.

Are there any practical limits on volumes of data when using IMPORTRANGE? Currently the raw data is reasonably normalised, so most reports will require several imports, with appropriate VLOOKUPs to join the data. Or can you suggest any better way of safguarding the raw data?

Love all this! I searched around looking for IMPORTRANGE info. I saw this seems to be the best page to post this. Thanks for the query limits and timeout specs. Very helpful.

I wondered if you know the best workaround to the IMPORTRANGE security issue. More info below.

What it is: For example: You have two Google Sheets files: ‘secret’ and ‘public’. Users include Friend, access to both, and Stranger, access only to the the public sheet. You go into the public sheet and use an IMPORTRANGE. The public sheet will ask for access to the secret sheet for the function. You approve. Now IMPORTRANGE is approved from public to secret. Then Stranger can go in and use IMPORTRANGE to show all of the content on the secret sheet. eek.

Workaround I’d use is to make a ‘middleware’ sheet. Friend puts an IMPORTRANGE call to the secret sheet from middleware only for the public data. Then Friend puts an IMPORTRANGE on the public sheet to ‘middleware’. So even if Stranger does IMPORTRANGE to other areas of the middleware, they’ll never see the other parts of the secret sheet. Not sure if that would work (without manual refreshing) or if there would be a work-around for that. Any thoughts?

If it is not posible to copy or edit your public sheet, you could simply hide row with IMPORTRANGE formula in it.

great tips!

One of my personal favourites is to keep the data on each tab as simple as possible (e.g. one table) and use multiple sheet tabs to bring together more complex data

Yes, this is a great approach to take

A few of the things I do with all Google Spreadsheets is:

1. Have an Intro sheet which explains the purpose of the sheet with links to where the data goes… like the webpage containing a table from the spreadsheet.

2. Have a version page which numbers significant revisions to the spreadsheet. The version number is displayed on the Intro page.

3. If the spreadsheet is used by other people, protect sheets and cells indicating where entries are to be made by using a standard colour. I use pale yellow for this and pale green, like the article, for indicating there is a formula behind the data. Often it is a good idea to provide a ‘Help’ link to a Google document giving further description.

4. Have a Calcs page which can be used for reference tables or Google id’s (on yellow cells) where information is brought in from other spreadsheets. Where there’s a Google id the next cell to the right pulls in some information from the referenced sheet like a date. Very useful if imported data is used on different worksheets.

5. If you have developed a script or a complex formula write a description a linked Google document so you can easily find it again when you need to use it again!

It also helps in building a library of scripts, you may come across, and which may be of use in the future. Don’t forget to include a back link to where you found it!

Spreadsheets are fun. Enjoy!

Great advice, Allan!

Thanks for sharing!

Hi Ben,

First off, your whole site is an invaluable resource, thank you very much for providing it.

Secondly, per item 11, I am always in need of an index column, but the problem I run into is that the data I work with often requires INSERTING rows, rather than adding more at the bottom.

I can’t think of any way to automatically re-index in a way that keeps the relationship between the index numbers and the information in the row they refer to.

Is there any type of formula that could do this automatically? I can’t figure out how to do it since it would have to be a weird combination of dynamic and static.

To date, I just manually re-do the index numbers of the whole column every time I need to insert a row.

I hope my question makes sense.

Thank you!

P.S. I love that CIFL uses your name his re-tweet demo sheets

Hi Aaron,

Assuming you have your IDs in column A, you could use a formula like one of these to automatically add an ID:

=SEQUENCE(COUNTA(B2:B))or

=ArrayFormula(IF(B2:B<>"",ROW(B2:B)-1,IFERROR(1/0)))Note this supposes that you don’t have any blank rows in your dataset in column B.

Hope this helps!

Ben

Thanks, Ben

It certainly helps, because it is a much easier way to automatically add the index numbers.

It also helps in that it seems I have discovered that what I am hoping for is not possible.

What I am hoping for is basically this:

ColA Col B Col C

INDEX Last Name Department

1 C HR

2 F HR

3 E HR

4 A Marketing

5 B Marketing

Where the order is established by the department head, who created the spreadsheet in the first place for his own needs, and who established the inter- and intra- departmental heirarchies.

Ok, so then we add a new assistant in HR, whose last name is D. I insert one row after row 3, fill in the employee contact details, and the ID automatically recalculates, like so…

ColA Col B Col C

INDEX Last Name Department

1 C HR

2 F HR

3 E HR

4 D HR

5 A Marketing

6 B Marketing

but now I want to sort by Last Name, but I want the IDs to travel with the rows they are currently assigned to, so that I can eventually re-set to the original organizational order…

ColA Col B Col C

INDEX Last Name Department

5 A Marketing

6 B Marketing

1 C HR

4 D HR

3 E HR

2 F HR

It seems impossible, though, unless I remember to Paste Values of ColA before I do any filtering or sorting.

There does not seem to be any kind of “conditional” formula that only re-calculates the ID if a row is added and not if a row MOVES based on a filter/sort of another column.

Sorry so long-winded! Thanks for taking the time to review!

-Aaron

hi ben, here on fred pike’s recommendation. where’s the best place to download spreadsheet data fo practice? thanks.

Hi Rafiki,

I use data.world, which has a huge online catalog of datasets (100s of thousands). It’s free on the community tier.

Cheers,

Ben

As someone who often has dozens (perhaps hundreds) of named ranges in a large sheet I am here to report on their limitations and annoyances.

My primary frustration is that dealing with names en masse is impossible. There’s no way, for example, to delete all #REF entries or to sort the list of names by their sheet location.

When copying a sheet, any names from the original are duplicated in the list, which is fair enough, but also indelibly prefixed with the name of the original sheet. I say indelibly because there is no way that I’ve found to remove the prefix from the name. Worse yet, the prefixes are ignored when sorting the name list and this can really mess with your equilibrium.

I have spent countless hours on clerical drudgery, cleaning and organizing my named ranges, and I believe that I’m better organized than most.